Critical Care

Photo by Getty Images

When Michael Halperin first heard Antonio Velasco, M.D. ’79, deliver a keynote address, he immediately recognized a powerful life story.

Halperin, a former screenwriter, spent years writing for TV, as well as several books and plays. This time, he wanted to tell Velasco’s story — one that involves working as a child as a migrant farmworker to overcoming the odds to attend college and then medical school, later using his practice to develop diagnostic protocols and treatment of toxic pesticide exposure among farmworkers.

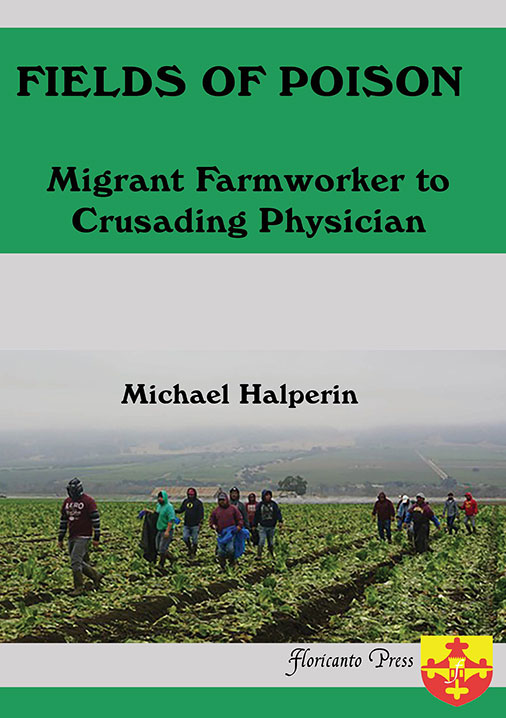

Originally envisioned as a film, the story eventually morphed into a biography: Fields of Poison: Migrant Farmworker to Crusading Physician (Floricanto Press, 2020).

Antonio Velasco with wife Isabel Guzmán-Velasco in 2014

Photo courtesy of Michael Halperin

Michael Halperin in 2020

Photo courtesy of Michael Halperin

“I thought it was another exciting possibility,” said Velasco, of the prospect of publishing his story. “I thought the book could make a difference in terms of educating people about the dangers of pesticides and the extreme conditions in which we lived as farmworkers. It was reminiscent of the Dust Bowl era and The Grapes of Wrath.”

In the beginning

To bring the book to fruition, Halperin undertook a major research project. In addition to interviewing multiple sources from Velasco’s life, including Velasco himself, he explored the United States’ relationship with Mexico throughout the years, especially in regard to labor.

“The history of the relationship between the United States and Mexico has always been very fraught,” said Halperin, who devoted the first chapter to this story. “And the history brought me to his father.”

Velasco’s father first came to the U.S. under the Bracero Program, which brought more than two million migrant farmworkers from Mexico between 1942 and 1964. When Velasco was 11, he joined his father in the U.S., along with his mother and siblings.

Fields of Poison tells the story of acclimating to a new life. Velasco, who had an innate talent for math and science, excelled in school — once the teachers recognized his abilities. Eventually, he was able to skip sixth grade and graduate high school in three years.

But during breaks, he and his siblings worked in the fields alongside their parents.

“The thing that impressed me most was the absolute determination that Antonio had from the time he was very young to overcome the life he was living,” said Halperin, adding that his experiences also gave Velasco a personal perspective on social justice, one that informed his later work.

The UC Davis years

After college at UC Santa Cruz — when he marched for farmworkers’ rights with Cesar Chavez — Velasco enrolled in medical school at UC Davis.

It was a charged time, one that saw many debates on race is school amid the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case that eventually went to the Supreme Court in 1978. (It upheld affirmative action.) Velasco said he gained a reputation as an agitator.

In 1974, he was among the UC Davis students and faculty who helped start Clínica Tepati, a student-run clinic that would address the healthcare gap in the Latino community of greater Sacramento. Velasco said he still considers its founding a milestone achievement in his career.

“I was able to develop skills above and beyond medical skills, above and beyond scientific education,” said Velasco. “I was able to see that if you approach people in a positive manner, things get done and people cooperate.”

When he graduated, his classmates selected him to deliver the commencement address. Looking back, another memory loomed largest.

“The most vivid memory of that graduation, besides my wife and young daughter coming up to get the diploma, was my dad, just radiating with pride,” said Velasco. “My advisor came up to me and said he’d never seen a father so proud. That just made me so happy because he had had doubts about me going to school. He was beaming, and it was wonderful.”

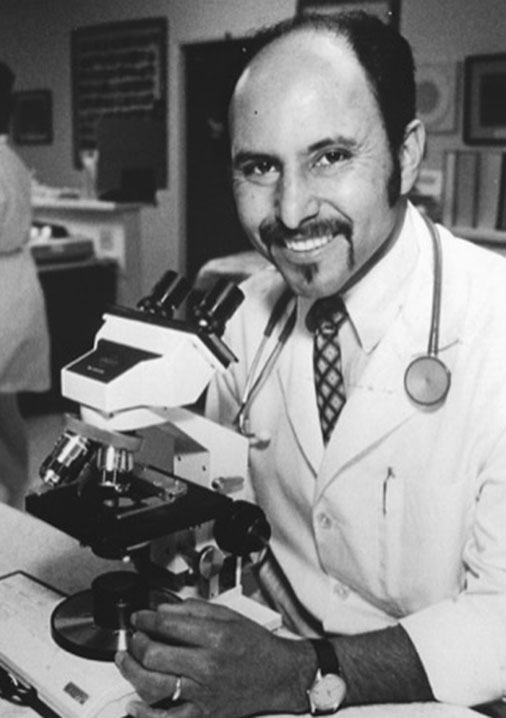

Antonio Velasco in 1981

Photo courtesy of Floricanto Press

Taking up a cause

Velasco joined Natividad Medical Center in Salinas upon graduation from medical school. Soon after, he opened a clinic to expand services for migrant farmworkers, while retaining his practice at Natividad.

In 1980, he treated a group of farmworkers for pesticide poisoning. Guided by data, Velasco and other doctors developed protocols for diagnosing and treating these patients. Velasco and a colleague also convinced them to continue care to learn more about exposure to pesticides and its impact.

“Because he had been a worker in the field and spoke the language, he was able to communicate with the workers the necessity for them to have their health followed once those incidents occurred,” said Halperin. “He and [another doctor], who had also been a field worker as a young man, listened to them and they knew the environment, the labor. They listened, and that had a tremendous impact.”

Thanks to the data gathered, Velasco and a team of advocates that included lawyers, politicians and community groups were instrumental in getting a posting ordinance passed in Monterey County. It required that signs be posted in fields of crops where pesticide has been applied and restricting access for a determined period.

Pesticide warning sign posted in Salinas, California

Photo by Getty Images

“Because of that, we were then able to go to the state legislature and pass state-wide regulations,” said Velasco. “At the end, we were able to prevail because of science.”

In 1991, he received the Humanitarian Award from the UC Davis School of Medicine Alumni Association, and in 1992, the California Academy of Family Practitioners named him Family Physician of the Year.

Here and now

Velasco resided and practiced in Salinas throughout his entire career. These days, he is retired and splits his time between his native village, Cofradía de Suchitlán in Mexico, and Capitola, California, with his wife, Isabel.

The village in Mexico is home to much of his extended family, and he lives in the house his father built in 1953.

“The woodwork and art in his house is absolutely beautiful,” said Halperin, who visited over the course of writing Fields of Poison. “It’s an expression of his personality.”

When asked about recounting his life story for the book, Velasco humbly credited certain people along the way who opened doors and offered opportunity for advancement.

“The odds of someone getting out of that cycle are incredibly difficult, almost impossible,” Velasco said. “My life has been a series of miracles. Serendipity has played a major role in my life.”