Painted from Memory

American artist and UC Davis professor emeritus Wayne Thiebaud turns 100 in November as his popularity continues to rise.

American artist and UC Davis professor emeritus Wayne Thiebaud turns 100 in November as his popularity continues to rise.

Photo: Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis

Professor Simon Sadler got to know Wayne Thiebaud before he actually met him.

When Sadler first joined the UC Davis faculty in the relatively analog era of the early 2000s, he spent a lot of time in the art department’s slide library culling images for his lectures.

“There would sometimes be this other guy in the room, and I never really knew who he was,” he remembered. “Maybe some sort of lecturer? A retiree?” Asked to write a catalog essay for a 2007 exhibition called “You See,” Sadler dug into UC Davis’ history as an art epicenter in the 1960s, when founding chair Richard Nelson recruited art faculty including Robert Arneson and Wayne Thiebaud to join the upstart department. The more Sadler learned, the more impressed he said he was.

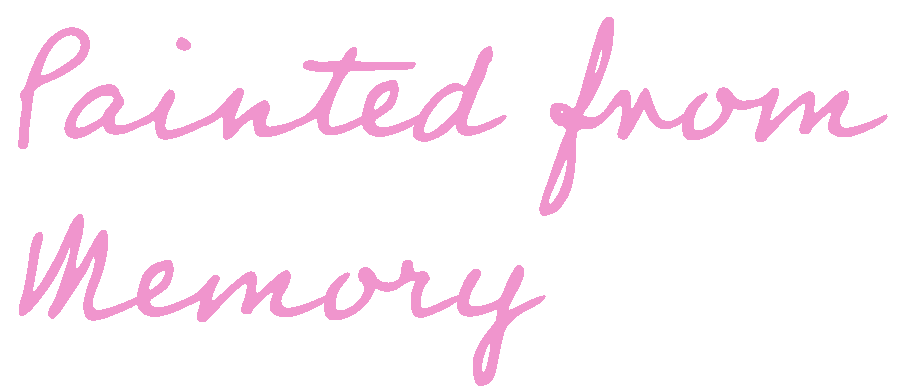

Wayne Thiebaud, Three Treats, 1975-76. Oil on panel. 10 1/2 x 11 7/8 in. Fine Arts Collection, Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis. Promised gift of Betty Jean and Wayne Thiebaud. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

“And then, one day, I’m in the slide library, and I’ve been mulling over Thiebaud’s titanic reputation, and I look across the table and realize … that’s Thiebaud!”

Although the realization took “an embarrassingly long time,” Sadler said, one of his initial impressions was correct: Thiebaud had retired in 1990 as professor emeritus, yet had continued to teach, unpaid, into the 2000s. While Sadler shuffled through dozens of slides, Thiebaud always knew exactly which handful he needed for, say, an exercise comparing works by Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt and Robert Rauschenberg. The fact that “someone of that stature is in the slide library putting slides together for an undergraduate lecture — that’s actual greatness.”

As Sadler would continue to learn, Thiebaud’s accessibility and “everyday-ness,” not to mention his intellect and razor-sharp memory, were key to both his art and teaching. “By keeping it immediate and real, whether it’s the observation of cream cake or the central importance of teaching freshmen, that is an ethos.”

Wayne Thiebaud will turn 100 on Nov. 15. He is one of America’s most famous living painters, beloved for his realist still-lifes depicting desserts and diner food, figurative works and California landscapes. His style is instantly recognizable, whether it’s the row of palm trees on the California Arts license plate he created in 1994 or iconic works that continue to set new auction records, such as Encased Cakes, or Four Pinball Machines (1962), auctioned by Christie’s in July. He has been awarded the National Medal of Arts (1994) and given the university’s highest honor, the UC Davis Medal (2009). He continues to be a prolific force, showing well-regarded new work at the Paul Thiebaud Gallery in San Francisco and Acquavella Galleries in New York.

These are the Wikipedia highlights of Wayne Thiebaud, American artist, that the world knows.

Yet when his 10th cover for The New Yorker magazine, of a double scoop of ice cream, was published in August, his contributor note simply read, “Wayne Thiebaud is a professor emeritus of art at the University of California, Davis.”

This low-key narrative of Wayne Thiebaud, professor, read familiarly to his friends, colleagues and former students. As they reflected on the impact he’s had during his four-decade tenure as he approached the landmark birthday, they described a man deeply dedicated to painting and teaching and whose lessons extended far beyond the classroom.

“Wayne Thiebaud is the best art historian I know,” said Rachel Teagle, founding director of the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at UC Davis. “His depth of knowledge is astonishing, and the most special moments in my relationship with him have been going to museums and looking at paintings with him.

“I called him Professor Thiebaud for the first couple of years I knew him — it’s how he encounters the world. He loves teaching, in part because he feels it’s a way for him to keep learning.”

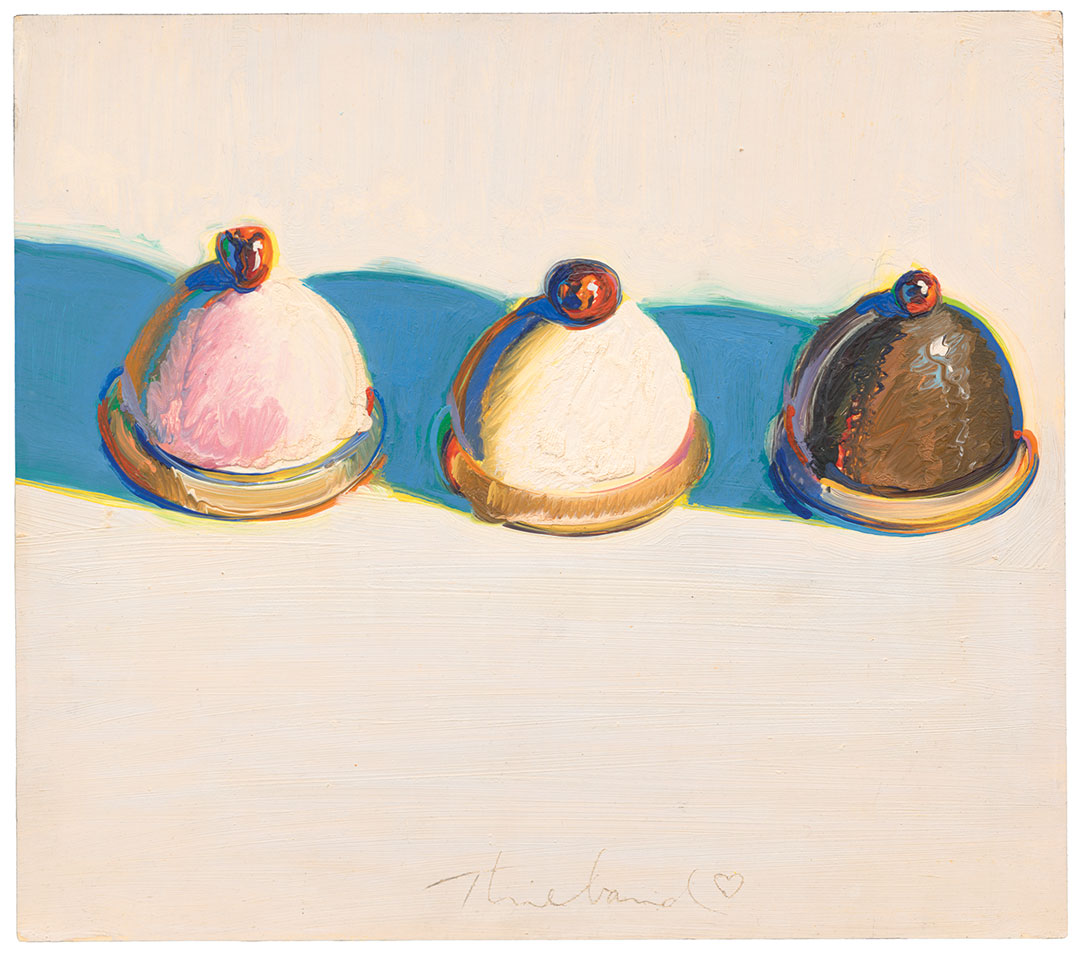

Professor Paul Beckman, far left, with Wayne Thiebaud in his Fifth Avenue studio, Sacramento, California. 1962/63. Courtesy of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation. Art © Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Wayne Thiebaud teaches class at UC Davis in the 1960s. Courtesy of UC Davis Special Collections.

Thiebaud’s route to teaching wasn’t a straight line. Born in Mesa, Arizona, in 1920, he grew in up Long Beach, California. While still in high school, Thiebaud had a summer apprenticeship with Walt Disney, drawing the “in between” cartoon panels that helped animate a character like Goofy. George Herriman, who drew the slightly surrealistic Krazy Kat comic strip (1931-44), was “a big hero of mine,” Thiebaud told art studio professor Hearne Pardee, who has interviewed him a number of times for the art journal The Brooklyn Rail. Krazy Kat was one of the first comic strips to be considered serious art and an influence on cartoonists ranging from Charles Schultz to Chris Ware. The concise form stayed with him and would resurface in his teaching.

“In the cartoon, it’s all about the frame: How do you get interest in the frame and get somebody to engage with the story and a narrative scene?” said Pardee.

Thiebaud joined the Air Force with the thought of becoming a pilot, but ended up as an illustrator with the First Motion Picture Unit from 1942 to 1945, drawing a comic strip called Aleck for his base’s newspaper. He held various commercial advertising jobs in New York and Los Angeles following his service, including at the Rexall Drug Company from 1946 to 1949. He decided to continue his schooling under the GI Bill in 1949, eventually earning his Bachelor of Arts from what was then Sacramento State College in 1951. He began teaching at the then-Sacramento Junior College while working on his Master of Arts degree (1952).

But the East Coast beckoned. He took a sabbatical in 1956 to live in New York, where he befriended abstract expressionists Franz Kline, and Elaine and Willem de Kooning, as well as artists then working in the pop art realm, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Willem de Kooning challenged him to “find something you love and try to deal with it — and not expect anything,” Thiebaud said in an interview with Apollo Magazine in 2017. Back home, he took de Kooning’s advice to find his own subject matter and way of rendering it.

Wayne Thiebaud, Cup of Coffee, 1961. Oil on canvas, 18 x 12 in. Fine Arts Collection, Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art. Gift of Fay Nelson. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Returning to the fundamentals, basic shapes such as triangles and cones became the slices of pie and other commonplace comestibles, with the exaggerated colors reminiscent of commercial advertising. Thiebaud feared this new direction might doom his career, yet “I just couldn’t leave it alone,” he has often said.

Around the same time, a new teaching opportunity emerged. Nelson, who had founded the UC Davis Department of Art in 1958, continued to lure artists like Roland Petersen to campus. Nelson actually offered Thiebaud the job twice. The second time, he sweetened the pot, promising the university would supply Thiebaud with a roll of canvas the size of a tree trunk for his “research” — i.e. painting — for which he would be able to spend about half his time.

“That was absolutely starkers,” Thiebaud told Sactown Magazine in 2018. “So I said, ‘I’m your man!’”

Teagle said Thiebaud is fond of telling the story about his first day on the job in 1960 — the day he fell in love with UC Davis. “He went to lunch at the Faculty Club, and of course didn’t know anybody,” she said. “So he sat down for lunch, and he ended up sitting next to a pomologist,” an expert in the science of cultivating fruit. “He loved that on his first day, he had this amazing lunch with a world expert in something totally different than what he did, that he was equally passionate about.”

By April 1962, Thiebaud had created a new body of work and gained a show at dealer Allan Stone’s New York gallery that would bring him national attention. Some of these seminal early works that made the painter “an overnight sensation a decade in the making,” said Teagle, were shown in 2018 at the Manetti Shrem Museum in “Wayne Thiebaud: 1958-1968.” They also reflect Thiebaud’s transition from impressionistic to representational paintings. Two depictions of candy counters, made several years apart, are painted “absolutely differently, and that’s a breakthrough moment,” said Teagle, who curated the exhibition.

At UC Davis, Thiebaud would go on to teach courses including “Introduction to Art,” “Introductory Figure Painting,” “Advanced Drawing and Painting,” “Printmaking,” and “Theory and Criticism: Painting and Sculpture.” He encouraged students to sketch daily, draw from memory, think critically, look deeply, embrace and learn from mistakes – and, when stuck, look to the masters for inspiration.

Conceptual artist Bruce Nauman, M.A. ’66, who served as one of Thiebaud’s teaching assistants, told art nonprofit Art21, “He showed you how to pay attention to what you were doing … a rare thing.”

Thiebaud has called teaching “the hardest work I’ve ever done,” next to painting. “But I love it, and I get something out of that I can’t really explain, but I think people that teach understand,” he said in a 2005 interview with KVIE.

Grace Munakata ’80, M.F.A. ’85, also a teaching assistant, kept her notes from that time and draws from those lessons as well as Thiebaud’s work in her classes.

“I’ve taught drawing and painting at CSU East Bay for over 30 years, and show students examples of how other artists have approached subject matter, composition, color and what is intrinsic about particular media.”

Vonn Sumner ’98, M.F.A. ’00, an artist who lives in Santa Ana and is a tenured professor at Fullerton College, has stayed in touch with Thiebaud. They exchange letters, and Sumner occasionally visits him to share paintings.

“Wayne’s generosity as a teacher extends seamlessly into his convivial collegiality as a fellow painter,” he said. “He regularly repeats the idea that painting seems to be at its best when there are groups or communities of like-minded people who are rigorously involved with painting and with exchanging ideas and energy.”

Article continues below, after sidebar

Pardee and Gina Werfel, an artist and UC Davis art professor who is married to Pardee, can attest to that. They first met Thiebaud as students at the New York Studio School in 1973. Thiebaud had been in residence and also taught the school’s Paris study abroad session, which Pardee and Werful helped run. Then they were recruited to join the Department of Art in 2000.

“When we first got together with Wayne and [his wife] Betty Jean, it amazed us how much they remembered!” Werfel said.

Both Pardee and Werfel used one of Thiebaud’s assignments for their own painting classes: drawing a glass of water. “He had them bring a plastic cup and put it up against a white sheet of paper so there was really no color at all; there was just the water. How do you see that? I always thought it was a great idea,” Pardee said.

They didn’t overlap with Thiebaud’s teaching years until, at his urging, the couple put together a seminar of four senior art majors in 2012. Although Pardee was listed as the instructor, Thiebaud came to every session and soon had the students “enraptured,” Werfel said.

“The assignments were things like ‘make a replica of one of your paintings at a different scale’ or ‘make a replica of one of your paintings but make all the colors either one shade darker or one shade lighter,’ ” said Kristen Sanders ’12, now a lecturer in drawing and painting at the University of Minnesota. “Picking one variable to change has been helpful when I’ve felt stuck in my work.”

A decade into the 21st century, Thiebaud continues to influence a new generation of artists by having stayed the course. Teagle said she looks forward to celebrating his centennial and impact with a forward-looking exhibition in early 2021 (see sidebar).

“Wayne Thiebaud was a champion for painting at a time when painting was perceived as old-fashioned,” Teagle said. “There were even grandiose statements that painting was over. And Thiebaud was a true believer and kept painting, because it’s what mattered to him. It’s his vision of why art is important and has meaning.”

He has also left a physical legacy on the campus and its contemporary art museum.

“The Manetti Shrem Museum was a dream for a very long time,” Teagle said. “Its champions — Margrit Mondavi, Wayne Thiebaud and Sandy Shannonhouse — really believed that UC Davis needed an art museum, and Wayne’s vision was that all students should have access to original works of art. Seeing, in person, something that’s been handmade can be an educational experience, an emotional experience and an enriching experience. He wanted UC Davis students to have access to the arts.”

When the museum was being designed, “our architects were looking at what Wayne Thiebaud loved about the Central Valley,” Teagle said. The museum’s color gradient logo and the building’s interplay of light and shadow are among the visible results. Thiebaud is also the preeminent donor to the university’s Fine Arts Collection, having given 392 works of art, including 83 of his own works.

An unfinished figurative painting of his late wife, Portrait of Betty Jean, hangs in the museum’s Paul LeBaron Thiebaud Collections Classroom. “That particular painting allows people to see some drawing and some mistakes, things that need to be corrected,” Thiebaud said in a 2016 UC Davis video interview announcing the gifts.

“But that’s the way in which students learn. The advantage of a classroom for a painting or drawing class is that you not only learn from the instructor, but you watch maybe 20 or even 30 students trying to doing the same thing you’re doing, and some of them will do it even better.”

Those who know him say Thiebaud readily admits there are always new things to learn.

“Every time he gets up from the lunch table, he’ll say, ‘OK, it’s time to go make some mistakes,’” Teagle said. “That means that he’s going to the studio.”

And while the art department’s slide library has been digitized, nearly two decades since Sadler’s first visits, the professor and chair in the design department said he thinks he may have finally answered the question of “Just how big a figure in art history can you become while still remaining an ordinary person?”

“Wayne could have left us,” said Sadler. “He can do and be wherever he wants, but he sticks around. He lives in Land Park, in Sacramento. It’s as though he figured out what matters was painting and teaching and collegiality.”