Does Widening Highways Ease Traffic Congestion?

It’s an age-old conversation starter: “How was traffic?” In California, and almost everywhere there is a big population, the answer is often, “terrible.”

According to an annual report by INRIX, a transportation analytics company, a typical driver in the United States lost 51 hours in traffic in 2022, up from 36 hours the previous year. In California, Los Angeles and San Francisco have the worst traffic, with drivers losing 95 and 97 hours, respectively.

“The U.S. is pretty car-oriented. I think there are a lot of people who would be happy to drive less if it was possible, but it’s just not possible for most of us,” said Susan Handy, professor of environmental science and policy at UC Davis, who offers new ideas for the well-documented problem in her recent book, Shifting Gears: Toward a New Way of Thinking about Transportation (The MIT Press, 2023).

For years, people have, erroneously, assumed that adding lanes to a highway will solve the congestion problem. In fact, the ideal solution would not only address the flow of movement, but also equity, safety and the environment.

The problem

The traffic conundrum is illustrative of the basic economic principle of supply and demand.

The law of supply and demand describes the economic relationship between the price of a product, its availability and the buyers’ demand for it. In relation to traffic congestion, if you reduce the price of driving (usually time), drivers will consume more of it.

People start making adjustments pretty quickly, Handy said. If the cost goes down, research shows they are going to make car trips they wouldn’t have otherwise made.

“The classic example I use is going [across the I-80 causeway] from Davis to Sacramento on Friday night, which no one would ever do because the traffic is so bad,” Handy said. “But if the traffic weren’t so bad, some of us would drive to Sacramento and take advantage of the wonderful restaurants they have there. People may shift the routes they take, they may shift their mode because some might have been using transit and now they’ll get back in their cars.”

Research proves that when roads are widened, drivers start to make more trips, make longer trips and choose the car more frequently — and the cycle of traffic continues. Handy said the effects include better access to farther locations, which leads to new developments and increased population — all leading to more drivers on the roads.

In fact, Handy’s research documents how a 10% increase in volume on the highway will, in the long run, lead to a 10% increase in the volume of driving. And then the traffic problem is back to where it started.

The alternatives

While alternatives depend on the goals of the area, Handy said, returning to the law of supply and demand means that the solution is to price the highway. Adding a toll to high-congestion roads would help ease traffic.

In the Davis area, officials continue to seek relief on congested highways. Caltrans has recently proposed what would be the Sacramento region’s first tollway on Interstate 80 from the Solano/Yolo county line, through Davis, across the causeway, to El Camino Road in Sacramento in both directions. A tolled express lane would be added in a $465 million construction project.

Handy said the proposal doesn’t go far enough.

By adding a lane to the existing highway, even with a tolled lane, the price of driving has been lowered for that road.

“Better than that would be to take an existing lane from what we’ve got and convert that to a toll lane,” Handy said. “And what I would like to see is: Let’s toll the whole thing.”

In addition to making driving less enticing by price, Handy said municipalities should consider other aspects of driving, including health, safety and equity. In her work, she has studied what California could gain from reducing car dependence.

She advocates for strategies such as implementing land-use policies that consider increased density and housing policies that foster a less car-dependent society. Investments in a transit system that includes walking and biking would allow for the positive benefits of physical activity over driving.

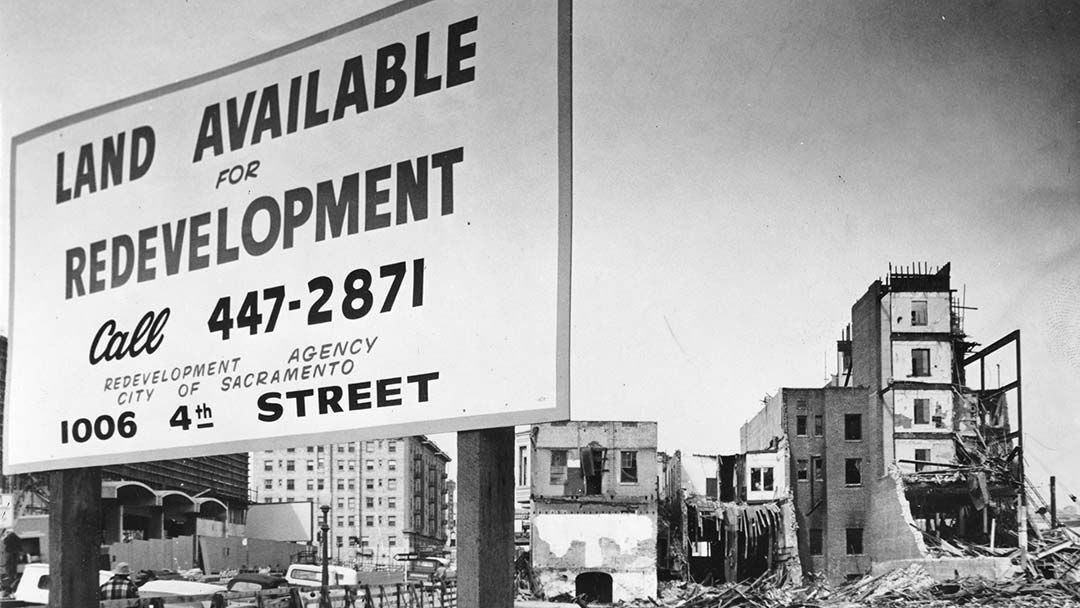

Handy and colleagues work with the California Air Resources Board to synthesize these strategies to help reduce driving. For Caltrans, they have done case studies of highways that were built years ago and analyzed what happened in California communities by them.

Handy highlights these issues in Shifting Gears, and the fact that old methods haven’t worked motivated her to write the book.

“We keep doing things the old way, and not solving any of our problems,” Handy said. “What we need to be doing is making it easier to not drive.”