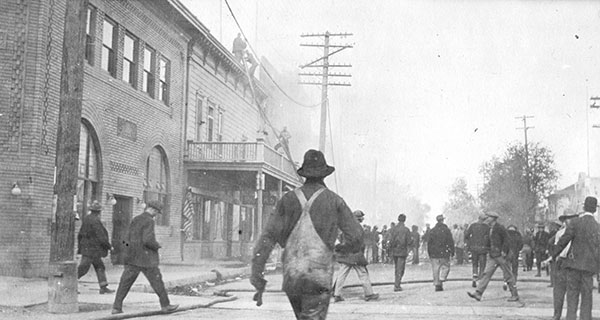

Above: Fire photo taken by UC Davis alumnus Harry Hazen after the November 1916 fire.

(Harry Hazen scrapbook / Special Collections, UC Davis Library)

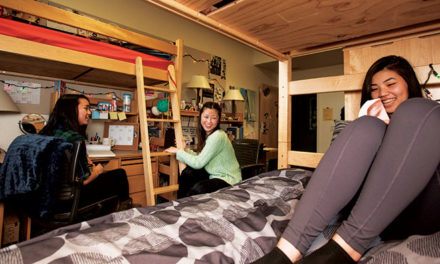

The First Century

How did Davis become a city?

Most people think it took half the town burning down to convince residents of what was then Davisville to incorporate 100 years ago.

“It was this day that created public sentiment to become a city,” Bob Bowen, a spokesman for the city of Davis, told a crowd at a showing of historical photos on March 28, the anniversary of the city’s incorporation.

The devastating blaze in 1916 destroyed half of downtown Davis, burning unchecked because the city had no pressurized water supply or fire department. Davis residents could only futilely toss buckets of water on the inferno until a Southern Pacific train with a firefighting rail car arrived from Sacramento. Newspaper accounts from the time speculated the fire easily could have been stopped with proper water lines and a fire department — things that come with incorporation.

Fire photo taken by UC Davis alumnus Harry Hazen after the November 1916 fire.

(Harry Hazen scrapbook / Special Collections, UC Davis Library)

The Varsity movie theater, circa 1951

(Special Collections, UC Davis Library)

Just four months after the 1916 fire, Davis residents voted to formally become a city (a 1911 vote failed 92-103).

Still, some historians say a pro-growth community spirit, and not a fire, convinced residents to vote to become a city.

“People buy a simple notion, which is a fire scared residents into voting to tax themselves,” said Professor Emeritus Dennis Dingemans, a former Davis planning commissioner and the director of the Hattie Weber Museum.

He cited burgeoning industry in the town (an almond-hulling machine developed in Marysville was being manufactured in Davis) and a community of steadfast supporters, led by Davis Enterprise Editor and Justice of the Peace William Scott.

Professor Emeritus John Lofland, who has written several books about Davis history, wrote in 2004 that Scott was the town’s “booster-in-chief,” and cited one of his first editorials, which suggested people should always shop locally and never speak ill of their town.

“We were a town of boosters,” Dingemans said.

One hundred years later, city leaders say that spirit is still alive.

“Davis still has many, many boosters — individuals who have the desire and ability to improve the community and usually have a project or vision that is shared by many others,” said Lois Wolk, who served as a Davis city council member and mayor before terms as a county supervisor and state legislator.

She said residents still strive to improve the town, citing as examples the 1993 construction of Sutter Davis Hospital and the regional water treatment plant completed in 2016.

On a smaller scale, former city council member Bill Kopper cited volunteer-service organizations, community-supported art galleries and other efforts to help the less fortunate.

“Davis is in every way still a town of deep citizen involvement in the community,” he said. “Everywhere you look people are volunteering to help.”

This year, boosters and casual observers alike will mark the centennial. A week after the centennial date, Davis city council members donned period costumes to reenact the first board of trustees meeting, complete with proposing ordinances to form a fire department and outlaw littering. The 2017 Picnic Day theme, “Growing Together,” acknowledged the centennial, and its parade featured former council members.

The city plans to dedicate a corner of Second and G streets as “Centennial Plaza,” with artwork and historical signs, and a time capsule is in the works. And not just history buffs are getting in the spirit: This spring Sudwerk Brewing Company developed a “centennial brew” as a limited-release beer.