What Can We Learn from Phoenix as Sacramento Area Temperatures Rise?

At 6:30 a.m. on a September morning in Phoenix, you can walk outside with your morning coffee and the day is already hot. Like 90 degrees hot.

“I call it Hot Land,” said Phoenix resident and community health advocate Stacey Champion. “It’s really like living in an oven for part of the year.”

Phoenix hasn’t cracked the code of how to live with extreme heat. Heat-related deaths across Arizona tripled between 2014 and 2017, from 76 deaths to 235. Most of those deaths were in Phoenix.

How Phoenix handles heat holds lessons for other warming cities like Sacramento, where both temperatures and populations are increasing.

Heat in perspective

By 2100, according to the 2018 Sacramento Valley Climate Change Assessment, the number of days that midtown Sacramento is expected to experience temperatures topping 104 degrees is expected to grow from four days per year to 40. That is similar to what Tucson experiences now and about half of what Phoenix deals with already.

From her office in Sacramento, Helene Margolis, an associate adjunct professor in the UC Davis Department of Internal Medicine, wants to be clear: “We’re here now. You don’t need 120-degree temperatures to have a huge public health impact.”

In 2006, a summer heat wave swept over most of California for an unprecedented two weeks, breaking temperature records and killing at least 600 people.

Margolis co-authored a study showing that the heat wave brought on about 1,200 additional hospitalizations statewide and 16,000 extra visits to the emergency room. Even in relatively cool San Francisco, temperatures as low as the 80s were unseasonably warm enough to increase ER visits and heat-related illnesses.

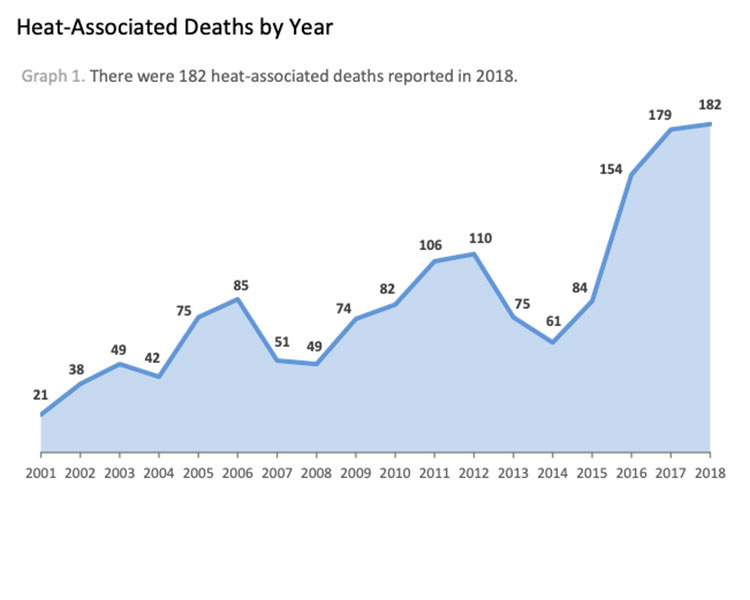

Data Sources: Maricopa County, Office of Vital Registration and Office of Medical Examiner; Arizona Department of Health Services, Office of VItal Registration

Tracking heat

As California was reeling from its heat wave, Arizona was in the middle of a major spike in heat-related deaths, as well, jumping from 42 deaths in 2004 to 85 in 2006.

Maricopa County, where Phoenix sits, knew that to manage a problem it had to be measured. The county became the first in the nation to develop a heat surveillance program to track the communities and demographics most affected.

“Every summer is different,” said Kathryn Conlon, who specializes in climate adaptation health with UC Davis Health and the School of Veterinary Medicine. “Surveilling alone doesn’t tell you how to intervene, but it tells you where you might be able to.”

Surveillance in Sacramento

Sacramento County just began to analyze heat surveillance data in the past several months using a program originally used to track flu in the region and, last year, wildfire smoke.

During heat events, the system tracks emergency room visits and heat-related illnesses, ambulance calls, and where they come from. It compares daily air quality and temperatures and provides demographics about who is being most affected.

“Until this point, what we had been looking at were the deaths, and those are few and far between in Sacramento,” said Olivia Kasirye, public health officer for Sacramento County. “Being able to look at this additional data means we’re not just looking at the tip of the iceberg anymore.”

Who is dying from heat in Phoenix?

As Maricopa County dug deeper into its heat surveillance data, surprising trends began to emerge:

- Forty percent of heat-related deaths happen indoors, mostly to elderly women living alone.

- People dying outdoors tend to be men, ages 24-45.

- Most people dying from heat have lived in the Phoenix area for 10 to 20 years. This demonstrates the false perception that residents acclimate over time.

An unsurprising finding? People already impacted by social, environmental and health disparities experience the worst impacts related to climate change and extreme heat, although no one is immune to them. In other words, the vulnerable are the most vulnerable.

While extreme heat and smoke events affect everyone, the unhoused population, for example, has nowhere to go.

“We have to think about heating and cooling as a social justice issue,” said Flojaune Cofer, senior director of policy at Public Health Advocates, a Sacramento-based nonprofit.

Cooling centers

Cooling centers are one tool cities use to help heat-vulnerable populations. These air-conditioned facilities — like libraries, senior centers and community centers — can be used during heat waves to cool down.

Maricopa County has dozens of cooling stations and hydration stations highlighted on a Heat Relief Regional Network Map.

Sacramento opens its handful of cooling stations when the forecast calls for highs above 105 degrees for three consecutive days and lows above 75 degrees.

Researchers and public health advocates point out several shortcomings to cooling centers that, if overcome, may help them become more effective:

- The centers often carry a stigma of being only for disadvantaged populations.

- They are rarely open past 5 p.m. — the hottest time of day for many western cities — due to staffing and funding needs.

- Pets are not often welcome, so their owners stay home with them.

- People aren’t always aware of open cooling centers, where they operate, or how to get there.

Some advocates say laws should prevent the power from shutting off in extreme heat the way some protect those in freezing temperatures.

Power shut-off protection

Many states have laws that prohibit utilities from shutting power off to people when temperatures drop below freezing.

In a city that lives and dies by air conditioning, Stacey Champion is fighting for a similar law to be in place for extreme heat in Arizona.

However the law plays out in Phoenix, it’s an issue warming cities are wise to consider, especially in places already facing affordable housing and homelessness issues.

“The affordable housing piece of this is massive,” Champion said. “The more people aren’t protected, the more people will die.”

Getting climate ready

For Sacramento to adapt and thrive in a warmer future, collaboration across agencies, institutions, jurisdictions and communities is vital to ensure that solutions are interwoven through all facets of life.

The Capital Region Climate Readiness Collaborative is working to raise awareness and engage a regional discussion about climate change as both a public health issue and a social justice issue.

“The longer we wait, the less opportunity we’ll have to address these issues,” Cofer said. “But some positive things are happening now.”

Read more:

For more on this story and the full Becoming Arizona series, see climatechange.ucdavis.edu.